If you pay any attention to the media, it would seem we have entered an age of prolific concussion and brain injury. The issue has been brought to the forefront, mainly through the coverage of concussions and their long term effects on sports people, with a focus on contact sports. But before we label the current incidences as a ‘concussion crisis’ with irrevocable consequences, it is important to know what a concussion actually is and how it differs from a mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI) or even a moderate to severe traumatic brain injury. Concussion and mTBI are often confused, even in medical literature, and the terms are often used interchangeably. However there are some important differences between the two.

According to the American Association of Neurological Surgeons, a concussion is defined as an injury to the brain that results in temporary loss of normal brain function. Concussions are usually caused by a blow to the head, acceleration or deceleration (whiplash), a projectile or an explosion. However this is not necessarily the criteria for a mTBI.

Dr Arthur Shores, a Clinical Neuropsychologist, points out the differences between the two medical conditions: ‘Concussion is the historical term representing low-velocity injuries that cause brain “shaking” resulting in clinical symptoms and which are not necessarily related to a pathological injury. In contrast, mTBI is part of a spectrum of injury severity that reflects a pathological injury. This is typically assessed by the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) and the Westmead PTA Scales (WPTAS and AWPTAS) that are widely used in emergency departments and brain injury units in Australia. The assessment of traumatic brain injury and classification of the severity of an injury is reflected both by the depth of disturbance in consciousness (coma), as well as the duration of post-traumatic amnesia (PTA).’

Mild TBI

The operational definition of mild TBI (Carroll et al, 2004) is defined by the World Health Organisation (WHO) Collaborating Centre for Neurotrauma Task Force on mTBI as follows:

‘mTBI is an acute brain injury resulting from mechanical energy to the head from external physical forces. Operational criteria for clinical identification include:

- One or more of the following: confusion or disorientation, loss of consciousness for 30 minutes or less, post-traumatic amnesia for less than 24 hours, and/or other transient neurological abnormalities such as focal signs, seizure, and intracranial lesion not requiring surgery;

- Glasgow Coma Scale score of 13–15 after 30 minutes post-injury or later upon presentation for healthcare.’[1]

Moderate to extremely severe TBI

Moderate TBI is defined by a disturbance in consciousness producing a GCS score of 9–12, and a period of persistent deficits in retaining new information and processing new memories (PTA) of 1–24 hours. Severe TBI is defined by a GCS of 3–8, and a period of PTA of 1–7 days. Very severe TBI is characterised by a period of PTA of 1–4 weeks. Extremely severe TBI is defined by a period of PTA of greater than four weeks. (Figure 1).[2]

Figure 1. Classification of traumatic brain injury severity.

| Mild | Moderate | Severe | Very Severe | Extremely Severe |

| GCS

13-15 |

GCS

9-12 |

GCS

3-8 |

GCS

3-8 |

GCS

3-8 |

| PTA

<1-24 hours |

PTA

<1-24 hours |

PTA

1-7 days |

PTA

1-4 weeks |

PTA

>4weeks |

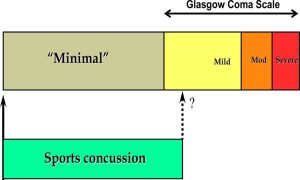

Concussion may be seen as a ‘minimal’ injury subset that falls below the threshold of mTBI (ie, GCS) score 13-15. This represents the majority of concussive injuries seen in sports (Figure 2).[3]

Figure 2. Sports concussion as minimal injury subset of mild traumatic brain injury.

Assessment of outcome

Recovery from a mTBI can vary, however generally speaking, the severity of the mTBI will have a direct impact on the likelihood of a positive recovery. Dr Shores states, ‘Concussion and uncomplicated mTBI generally lead to full recovery, however repeat concussions and complicated or more severe injuries can lead to long term functional impairment.’ Dr Shores advises caution and care when evaluating an injury, as there are dangers in both over-estimating and under-estimating brain injury severity, particularly based on duration of PTA. ‘Duration of PTA provides a guideline to the severity of brain impairment and has been shown to be a useful outcome predictor of cognitive-behavioural-social dysfunction, with longer duration of PTA predicting a worse outcome. A careful scrutiny of the results of existing measures is necessary in determining severity of the injury. In contrast to mTBI, Moderate to Very Severe traumatic brain injuries are expected to have more permanent neurocognitive disorder than would be expected in claimants with mTBI. Neuropsychological assessments are useful in determining the severity of the injury and evaluating the outcome,’ Dr Shores states.

If you need a neuropsychological assessment regarding a concussion or mTBI, please contact our experienced team at MedicoLegal Assessments Group.

[1] Carroll, L.J., Cassidy, J.D., Holm, L., Kraus, J., & Coronado, V.G. (2004). Methodological issues and research recommendations for mild traumatic brain injury: The WHO collaborating centre task force on mild traumatic brain injury. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine, S43, 113-125.

[2] Neuropsychological Assessment of Children and Adults with Traumatic Brain Injury: Guidelines for the NSW Compulsory Third Party Scheme and Lifetime Care and Support Scheme, 2013, MAA, Editor. 2013, Sydney.

[3] McCrory, P., Meeuwisse, W.H., Echemendia, R.J., et al. What is the lowest threshold to make a diagnosis of concussion? British Journal of Sports Medicine, 47, 268–271.